The Unsung Saga of Indian Resilience: Defying Early Arab Invasions

The Invincible Spirit of Bharat: Resistance That Redefined History.

Introduction: The Unsung Saga of Indian Resilience

The 7th century CE witnessed the meteoric rise of Islam, imbuing its early adherents with a formidable "war-like spirit and national consciousness" that propelled a rapid and unprecedented expansion. Within a mere century of Prophet Muhammad's passing, the Umayyad Caliphate had forged an empire stretching from the Iberian Peninsula in the west to the very frontiers of India in the east. This swift territorial acquisition overwhelmed established powers like Persia and Byzantium, whose long-standing empires succumbed with remarkable speed. India, historically renowned for its immense wealth, fertile lands, and established trade networks, naturally emerged as a prime target for these burgeoning expansionist ambitions.

However, the historical narrative of this period often overlooks a crucial distinction: India's response to these incursions was markedly different from that of other regions. Unlike many territories that rapidly assimilated into Islamic rule and underwent profound cultural and religious transformations, India mounted a sustained and formidable resistance. This unique resilience meant that even after centuries of subsequent Muslim presence, Northern India largely retained its predominantly non-Islamic character, a stark contrast to the widespread Islamization observed from the Straits of Gibraltar to the Indus River. This historical reality compels a re-evaluation of simplistic portrayals of ancient Indian society as passively accepting foreign dominance. Instead, the evidence points to a fierce spirit of defense and a deep-seated determination to preserve its distinct religious and cultural identity.

The term "Avengers of Ancient India" serves to capture the collective and individual spirit of defense demonstrated by various Indian kingdoms and their leaders during this tumultuous period. It refers to the multi-front, multi-generational effort to repel invaders, often through strategic alliances and confederacies, showcasing remarkable strategic brilliance and unwavering courage. This report aims to illuminate these often-understated chapters of Indian history, emphasizing the active role played by Indian polities in shaping the outcomes of these early encounters, thereby presenting a more complete picture of a civilization that actively defended its heritage against a powerful global force. The sustained and unique resistance encountered by Muslim armies in India, unparalleled in other conquered lands, suggests that the underlying nature of Indian society, its military capabilities, and its political organization, despite internal divisions, possessed an inherent capacity for endurance and adaptation not observed elsewhere. This distinctiveness immediately reframes the historical understanding from one of inevitable conquest to one of determined, albeit sometimes costly, defiance.

The First Wave: Sindh and the Initial Encounters (7th-8th Century CE)

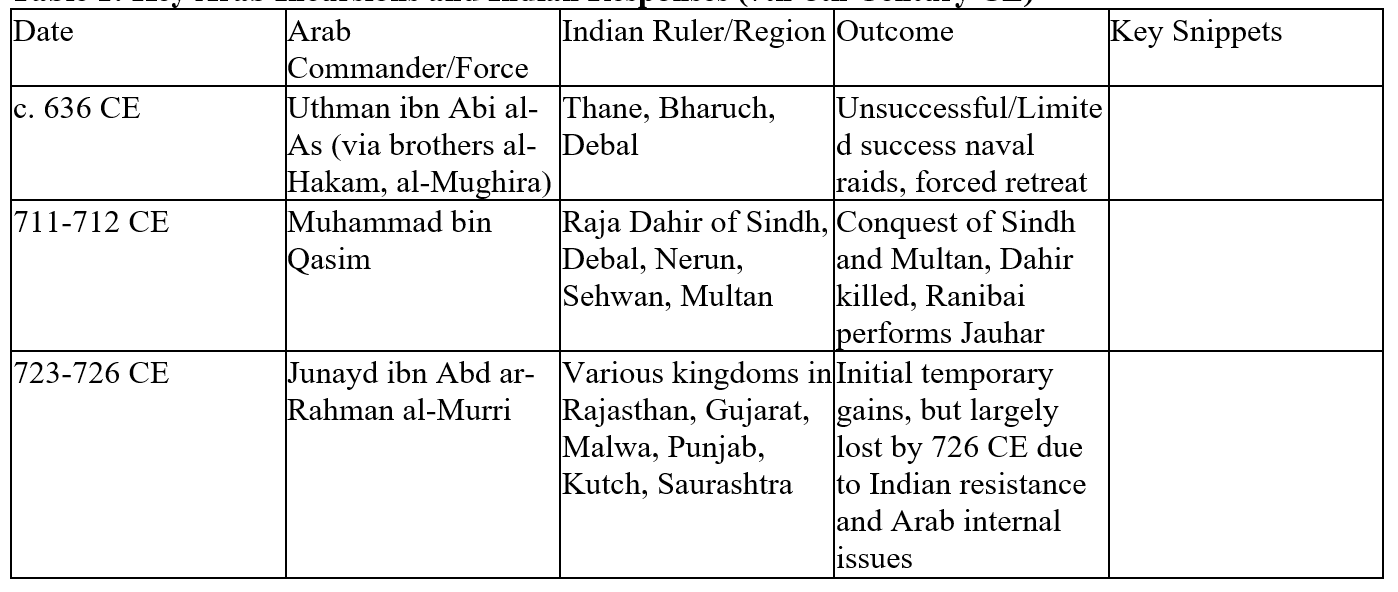

Early Arab Probes and Motivations

The earliest recorded Arab incursions into the Indian subcontinent predate any significant land-based military advance, occurring around 636/7 CE during the Rashidun Caliphate. These were primarily naval expeditions dispatched by Uthman ibn Abi al-As al-Thaqafi, the governor of Bahrain and Oman, targeting key port cities such as Thane (near modern-day Mumbai), Bharuch (in Gujarat), and Debal (near present-day Karachi). These initial raids, often undertaken without the explicit sanction of Caliph Umar, were likely driven by the pursuit of plunder or the strategic necessity of suppressing piracy to safeguard vital Arabian trade routes across the Arabian Sea, rather than signaling the commencement of a full-scale conquest of India. Historical accounts suggest that many of these early attempts were unsuccessful, often forcing Arab forces to retreat.

The Conquest of Sindh: Raja Dahir's Isolated Stand

By the early 8th century, the broader Indian subcontinent was characterized by political fragmentation, with numerous states engaged in internal competition for power and prestige. Sindh, despite its economic prosperity and active foreign trade, was particularly vulnerable due to its internal social divisions and an unstable rule under Raja Dahir, who had only recently ascended the throne after a contested succession. The immediate catalyst for the full-scale Umayyad invasion was the looting of Arab ships near Debal by Sindhi pirates. These ships were reportedly carrying valuable gifts from the King of Ceylon intended for the Caliph and Hajjaj, the powerful governor of Iraq. Raja Dahir's subsequent refusal to compensate for the losses or to control the pirates provided the Umayyad Caliphate, under Caliph Walid and Hajjaj, with the necessary justification for a military intervention.

Muhammad bin Qasim, a young yet highly capable Arab military commander, spearheaded the invasion in 711 CE, leading a substantial force that included Syrian cavalry, camel riders, and advanced catapults. His campaign was characterized by a systematic conquest of key strongholds: first Debal, where the use of catapults proved decisive , followed by Nerun, Sehwan, and ultimately Multan. Raja Dahir, despite initial strategic passivity, eventually engaged the Arab forces in a heroic stand at the Battle of Rawar in 712 CE, personally leading his army from the front atop an elephant. However, his forces were ultimately overcome. Factors contributing to their defeat included the panic caused by a wounded elephant, the superior military tactics of the Arabs, and reports of internal treachery. Dahir was killed in battle, and in a profound act of defiance, his widowed queen, Ranibai, along with numerous other women, performed Jauhar—a collective self-immolation—rather than surrender the fort. Multan, famously dubbed the "City of Gold" by Qasim, eventually fell after its water supply was cut off, reportedly due to information provided by a traitor. The success of the Arabs in Sindh has been attributed to Raja Dahir's unpopularity, the existing sharp social divisions within Sindh, and the Arabs' superior weaponry, cavalry, military strategies, and fervent religious zeal.

The Immediate Aftermath: Arab Attempts to Push Beyond Sindh

Following the conquest, Sindh and Multan were formally established as an Islamic province. Arab military officers were appointed to govern the newly formed "Iqtas" (districts), while local Hindu officers continued to administer the subdivisions. A notable policy implemented by Muhammad bin Qasim, under the direction of Hajjaj and the Caliph, was the classification of Hindus as "people of the book" (Zimmis). This allowed them to practice their faith upon payment of Jizya, a religious tax, a policy considered more lenient than later Islamic administrations. Muhammad bin Qasim's successful campaigns, however, were abruptly terminated by his dismissal and subsequent death in 715 CE, following the ascension of the new Caliph Suleiman, an adversary of Hajjaj's family.

Despite the initial foothold in Sindh, Arab attempts to expand deeper into the Indian subcontinent encountered significant and ultimately insurmountable resistance. Governor Junayd ibn Abd ar-Rahman al-Murri, appointed in 723 CE, launched extensive campaigns into regions including Rajasthan, Gujarat, Malwa, Punjab, Kutch, and Saurashtra, achieving temporary conquests in many areas. However, historical records indicate that by 726 CE, many of Junayd's gains were reversed. Arab sources remain somewhat vague on the precise reasons, mentioning that Caliphate troops, often drawn from distant lands like Syria and Yemen, abandoned their posts in India and refused to return. This suggests a combination of factors, including potential Indian revolts and significant internal challenges within the Arab forces themselves.

The initial Arab conquest of Sindh, while a military victory, ultimately proved to be a strategically isolated event. The failure of the Arabs to expand significantly beyond this region, despite their initial success, was a critical turning point. This outcome was not merely due to internal issues within the Arab Caliphate, such as Muhammad bin Qasim's abrupt removal and subsequent internal conflicts among Arab officers. The limited financial resources of Sindh itself also posed a challenge, making it difficult for the Caliphate to sustain a large administrative and military presence for further expansion. Crucially, the primary reason for this limited expansion was the "valiant efforts" of powerful Indian dynasties like the Chalukyas, Rashtrakutas, and Gurjara Pratiharas, who actively thwarted their advances. This "failure" or "limited success" in India stands in stark contrast to the rapid and widespread conquests and subsequent cultural transformations observed across West Asia and North Africa. It demonstrates that the Indian subcontinent, unlike other regions, presented a unique and formidable barrier to the Caliphate's expansion. This anomaly indicates that the Indian political, military, and societal landscape possessed an inherent resilience that was activated beyond Sindh, setting the stage for the more organized and successful resistance that forms the core of this report. It highlights that the defenders of India were not just reacting to incursions but actively containing a global power.

Table 1: Key Arab Incursions and Indian Responses (7th-8th Century CE)

The Bulwark of Bharat: Dynasties that Held the Line

The narrative of Indian resistance is defined by the emergence of powerful regional dynasties that acted as formidable bulwarks against Arab expansion, preventing the deep penetration seen in other parts of the world.

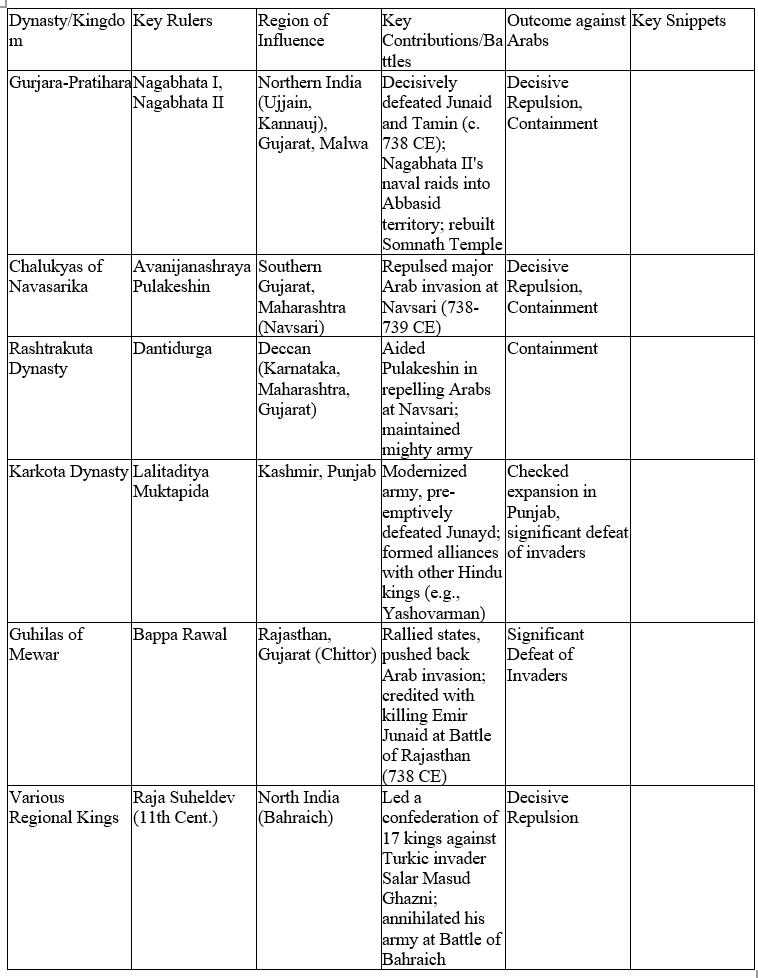

The Gurjara-Pratiharas: Guardians of the North

The Gurjara-Pratiharas, who governed extensive territories in northern India from the 8th to the 11th centuries, played an indispensable role in safeguarding the subcontinent against Arab invasions, effectively serving as a "mainstay" of India's defense for three centuries. At their zenith, the Pratihara empire commanded a territorial expanse rivaling that of the Gupta Empire, stretching from the borders of Sindh in the west to Bengal in the east, and from the Himalayas in the north to beyond the Narmada River in the south.

Nagabhata I (c. 730–756 CE) was instrumental in containing Arab armies attempting to advance east of the Indus River. In a pivotal engagement around 738 CE, Nagabhata I led a confederacy that decisively defeated a large Arab army commanded by Junaid and Tamin during the Caliphate campaigns in India. This formidable Arab force comprised Syrian cavalry, local Arab contingents, converted Hindus from Sindh, and various foreign mercenaries. The Gwalior inscription famously records that Nagabhata "crushed the large army of the powerful Mlechcha king," effectively halting Arab expansion from Sindh.

Nagabhata II (c. 805 CE onwards) further consolidated Pratihara control across Western, Central, and Northern Bharat. A less commonly highlighted aspect of his reign involves his strategic offensives, particularly a series of "brilliant naval raids across the Middle East" (targeting Iraq, Iran, and Arabia) between 816 and 820 CE. These operations, documented in Arabic and Persian records, aimed to disrupt Abbasid commercial shipping and military supply lines, liberate parts of Sindh, and establish military superiority to deter future incursions. Nagabhata II also successfully repulsed an Arab invasion with the support of his Chahamana and Guhila feudatories and is credited with rebuilding the Somnath Temple.

The Gurjara-Pratiharas' military prowess was underpinned by a robust organization and efficient administration. They maintained a large standing army, notably possessing a superior cavalry force that was lauded by Arab chroniclers as unmatched among Indian princes. Their administrative system, which drew upon and refined practices from earlier Gupta and Harsha empires, was crucial to their defensive capabilities. They strategically fortified key areas, particularly in the northwest, to serve as strongholds against invasions.

The proactive defense and the development of naval power by the Pratiharas represent a significant strategic innovation in ancient Indian warfare. While historical accounts often focus on Indian kingdoms repelling invasions, the detailed descriptions of Nagabhata II's offensive naval raids deep into Abbasid territory reveal a departure from a purely defensive posture. The ability to conduct such distant operations stemmed directly from the Pratiharas' conquest of the Gujarat-Saurashtra region, particularly Kathiawad, which possessed a long coastline and established seafaring traditions, thereby enabling the establishment of a formidable Pratihara navy. This naval capability was not merely for coastal defense but was strategically employed to project power. The objective was to severely disrupt Arab commercial shipping and military supply lines, which were vital for sustaining their garrisons in Sindh, and to establish a military dominance that would deter future incursions. This demonstrates a sophisticated understanding of logistics and economic warfare. This approach challenges the common perception of ancient Indian warfare as solely land-based and reactive. It highlights a proactive, multi-domain strategic approach, indicating a level of military sophistication and foresight often overlooked. The defenders of India were not just guarding their borders but actively striking at the enemy's logistical and economic heartland, showcasing a strategic depth that contributed significantly to the containment of Arab expansion.

The Chalukyas and Rashtrakutas: Southern Sentinels

The powerful dynasties of the Deccan, namely the Chalukyas and later the Rashtrakutas, played a critical role in halting Arab expansion into South India, effectively forming a southern bulwark against the invaders.

The Chalukyas of Navasarika, a branch of the larger Chalukya dynasty, were particularly prominent in this defense. Avanijanashraya Pulakeshin, a general serving the Chalukya king Vikramaditya II, gained renown for decisively repulsing a major Arab invasion near Navsari in Gujarat during 738-739 CE. This Arab force had previously plundered several kingdoms, including the Saindhavas, Kachchhelas, Saurashtra, Chavotkas, Mauryas, and Gurjaras, before being confronted and defeated by Pulakeshin's forces. So significant was this victory that Vikramaditya II eulogized Pulakesiraja as a "solid pillar of Dakshinpath" and "defeater of those who cannot be defeated".

The rise of the Rashtrakuta Dynasty, which eventually supplanted the Chalukyas, was also intrinsically linked to their participation in resisting the Arabs. Dantidurga, initially a feudatory of the Badami Chalukyas, is mentioned in some historical sources as having provided crucial aid to Pulakesiraja during this critical defense. The Rashtrakutas were known for maintaining a formidable army, with all ministers reportedly undergoing military training, ensuring a high state of readiness.

Southern Indian kingdoms, despite the climate being less conducive to extensive horse breeding, compensated by focusing on developing strong elephant corps, well-trained infantry, and capable navies. The Chalukyas, for instance, were recognized for their effective heavy cavalry and sophisticated siege warfare techniques. Their rivals, the Pallavas, developed a formidable navy capable of executing amphibious assaults, demonstrating a multi-front strategic capability. The constant conflicts and intense rivalries among these southern powers, while at times weakening them, paradoxically spurred remarkable innovations in military technology, fortification design, and administrative systems, necessitating continuous adaptation and improvement in warfare.

A notable aspect of Indian resistance was the complex interplay between inter-dynastic rivalry and the occasional, yet crucial, formation of collective defense. India was indeed characterized by political fragmentation, with numerous states "competing with each other" and engaging in "persistent fighting among them for power and glory". This disunity is frequently cited by historians as a significant weakness. However, in the face of the Arab invasion, multiple confederacies were formed, often involving traditionally rival kingdoms. The existential threat posed by the Arab invaders, characterized by a "fanaticism" and a perceived lack of "rules, honor, and code" that differed starkly from traditional Indian warfare, compelled these otherwise competing kingdoms to temporarily set aside their differences. The severity and distinct nature of this external threat acted as a powerful unifying force, overriding internal rivalries to forge defensive alliances. This highlights a critical, often paradoxical, dynamic in ancient Indian geopolitics. While internal divisions were undeniably a vulnerability, a shared civilizational identity and the perceived ruthlessness of the external threat could galvanize a collective response. The defenders of India were not a single unified force but a network of disparate powers capable of temporary, yet remarkably effective, unity when confronted with a common, existential danger. This explains why, despite internal strife, India could mount such a sustained and geographically widespread resistance.

Kashmir and Other Regional Powers: A Multi-Front Defense

The arc of Indian resistance extended far beyond the Pratiharas and Deccan powers, encompassing a multi-front defense that stretched from Kashmir in the north to Karnataka in the south.

Lalitaditya Muktapida of Kashmir, an influential ruler of the Karkota dynasty in the 8th century CE, played a significant role in checking Arab expansion in Punjab. Recognizing the Arab advantage in cavalry, Lalitaditya undertook a modernization of his army, effectively integrating war elephants with formidable contingents of horsemen and foot soldiers. Demonstrating audacious strategic foresight, he pre-emptively struck Junayd's forces, inflicting a crushing defeat before the invasion could fully materialize, and subsequently returned triumphantly to his capital. Lalitaditya also forged crucial military alliances with other Hindu kings, sharing intelligence gleaned from his past campaigns. He notably collaborated with Yashovarman of Kannauj to decisively defeat Arab advances towards Central India.

Bappa Rawal of Mewar, a legendary figure also known as Kalbhoja, emerged as a key leader in the 8th century. He successfully rallied various smaller states across Rajasthan and Gujarat, orchestrating a powerful pushback against the Arab invasion that had threatened Chittor. Bappa Rawal is credited with personally killing the Arab leader Emir Junaid during the Battle of Rajasthan (738 CE), a conflict where an estimated 5,000-6,000 Rajput-Gurjar infantry and cavalry confronted a much larger Arab force of over 30,000. This battle delivered a "body blow" to the Arab invasion, compelling them to retreat to the west bank of the Indus River.

Other regional powers also made significant contributions. The Solankis, for instance, provided crucial support in the resistance efforts in Rajasthan and Gujarat. Later, the 11th century witnessed continued regional unity against invaders, exemplified by the confederation led by Raja Suheldev against the Turkic invader Salar Masud Ghazni. This formidable alliance of 17 Hindu kings completely annihilated Masud's army at the Battle of Bahraich, serving as a powerful testament to the enduring capacity for collective resistance in India.

Table 2: Major Indian Dynasties and Their Contributions to Resistance

Anatomy of Resilience: Strategies, Society, and Spirit

The enduring resilience of ancient India against Arab invasions was a complex interplay of military strategies, societal structures, and an unyielding spirit of defiance.

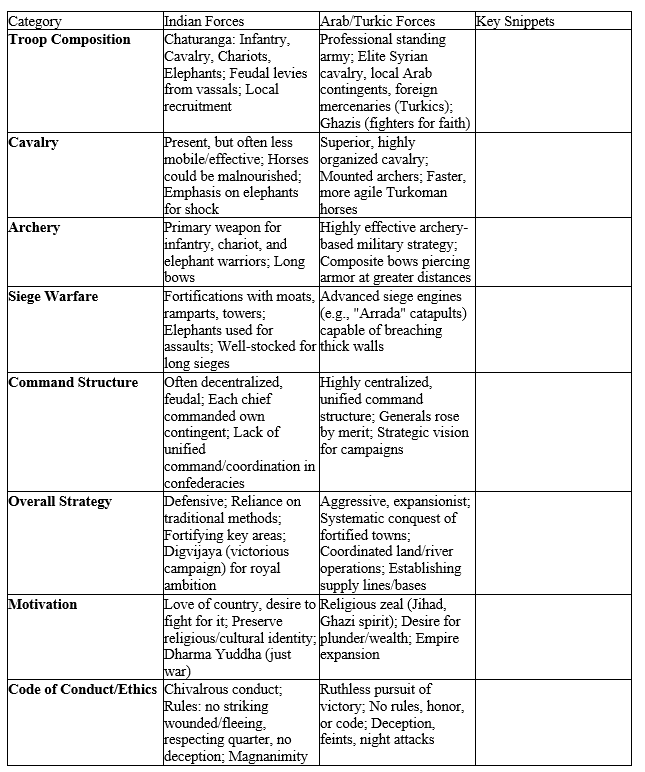

Military Innovations and Adaptations

Ancient Indian armies were traditionally structured around four principal arms (chaturanga): infantry, cavalry, chariots, and elephants. War elephants, in particular, were highly valued for their immense destructive power, their psychological impact on the enemy, and their utility as mobile command centers. While chariots initially held prominence, elephants had largely superseded them as the elite arm by the 6th century BCE. Indian forces also demonstrated a sophisticated understanding of battlefield formations, employing intricate vyuhas such as Chakra, Suchi, and Padma, which were adapted based on terrain and enemy composition. Cavalry gained increasing importance, especially under Rajput rulers, and some Indian commanders, like Lalitaditya Muktapida, innovatively combined elephants with formidable horsemen to counter Arab cavalry superiority.

Defensive fortifications and siege warfare were integral to Indian military strategy. Forts were strategically constructed with natural advantages in mind, heavily supplemented by man-made defenses such as moats, ramparts, towers, and multiple gates, providing crucial shelter and serving as chokepoints against invaders. These strongholds were meticulously stocked with food and weaponry to withstand prolonged sieges. Assaults on fortified positions often leveraged elephants, and archers played a vital role in both offensive and defensive operations.

In contrast, Arab military forces possessed distinct strengths and tactics. They were characterized by superior arms, highly organized cavalry, and effective military tactics, often fueled by intense religious zeal. Arab armies employed a professional standing force with disciplined cavalry and archers, utilizing swift hit-and-run tactics and mounted archery that proved highly effective against traditional Indian infantry formations and war elephants. They also brought advanced siege engines, such as the formidable "Arrada" catapult, capable of breaching thick fortifications. Their unified command structure and broader strategic vision, which included securing supply lines and establishing forward bases, contrasted sharply with the more feudal and often fragmented nature of Rajput armies.

Despite these strengths, Indian forces faced inherent challenges and perceived weaknesses. Indian kingdoms were frequently fragmented and embroiled in internal conflicts, often hindering their ability to effectively pool resources and present a united front. Historians note a "lack of unified command and coordination" among Rajput armies, a disadvantage when facing the cohesive Turkish forces. Furthermore, a reliance on traditional warfare methods and a deeply ingrained "code of chivalry" sometimes proved to be a tactical liability. This code often dictated rules of engagement that forbade attacking wounded or fleeing enemies, or employing deception, which could be ruthlessly exploited by an adversary described as recognizing "no moral or ideological scruples" in the pursuit of victory.

The challenges faced by Indian forces highlight a profound clash of military philosophies and cultural values. While Indian armies possessed a long-standing tradition of sophisticated military organization, including diverse troop types, intricate formations, and extensive fortifications , certain aspects of their approach proved problematic against the Arab and later Turkic invaders. The reliance on war elephants, for instance, could be exploited, as these animals were susceptible to panic from new technologies like gunpowder (though gunpowder was a later development, the principle of psychological impact applied). The use of heavy swords, while symbolizing strength, sometimes limited agility compared to the lighter, more flexible weapons of the invaders. More significantly, the "chivalrous conduct" embedded in Indian military tradition meant that warriors often adhered to specific rules of engagement—such as not striking a wounded enemy, respecting those asking for quarter, and avoiding deceptive tactics —that were not reciprocated by their adversaries. This directly contrasted with the Arab and Turkic forces, who were often described as "ruthless" and driven by "fanaticism," operating with "no rules, no honor and no code". This ethical framework, while admirable and deeply rooted in Hindu traditions of dharma yuddha (just war) , could be strategically exploited by an unconstrained adversary. This reveals that Indian resilience was not simply about military might but also about the kind of warfare they were prepared to wage. The defenders were, in a sense, constrained by their own moral and ethical code, which, while preserving their cultural identity and internal cohesion, sometimes placed them at a tactical disadvantage against a more pragmatic and religiously zealous foe. This deepens the understanding of the nature of the resistance, highlighting that cultural values can both strengthen and, paradoxically, hinder military effectiveness in certain contexts.

Societal Foundations of Resistance

A fundamental pillar of Indian resilience was the "resolute determination of the Indians to preserve their religious and cultural identity". Hinduism, characterized by its strong tenets of tolerance and its capacity to absorb diverse perspectives, enabled the civilization to withstand successive waves of external onslaughts without being completely subsumed. Despite centuries of foreign rule, core Hindu values remained "irrepressible". This deep cultural and religious rootedness provided a powerful, decentralized form of resistance, effectively preventing widespread conversions and cultural obliteration.

The significance of temples and local institutions cannot be overstated. Temples were far more than mere religious sites; they functioned as vital social, economic, and cultural centers that played a "great strengthening factor in keeping the people united". They served as hubs for religious discourse, music, dance, and other fine arts, receiving patronage from both the state and local communities. Temples provided employment, institutionalized social hierarchies, and acted as nuclei for society, directly involved in the economic, political, and cultural life of the populace. This made them crucial bastions of cultural continuity and, by extension, resistance.

While India was indeed politically fragmented, and the caste system was present, it is important to note that it was not as rigid in the early medieval period as it became in later centuries. This allowed for intercaste marriages and the absorption of foreigners into Hindu society. Women generally occupied a respectable place in society, received education, and participated in social, religious, and even administrative functions. However, the "sharp social divisions" and Raja Dahir's unpopularity in Sindh were specifically cited as factors contributing to the initial Arab success in that region, highlighting a contrast with the broader, more unified cultural front observed elsewhere.

The apparent contradiction between India's political fragmentation and its sustained resistance can be understood by recognizing a powerful underlying dynamic: deep cultural cohesion. While political unity was often lacking at the imperial level, and states were frequently "competing with each other" and engaged in "persistent fighting" , a strong, deeply ingrained cultural and religious identity provided a powerful, decentralized form of societal cohesion. Hinduism's inherent tolerance, adaptability, and deep roots allowed it to act as an enduring force. Temples, as central social and cultural nuclei , reinforced this identity at the local level, serving as resilient centers that preserved traditions and beliefs even when political structures faltered. This suggests that civilizational resilience is not solely dependent on centralized political power or military might. A robust and adaptable cultural and religious identity can act as a powerful, enduring form of resistance, preventing complete cultural assimilation or widespread conversion, even in the face of military setbacks. The defenders of ancient India were not just armies on the battlefield but the very fabric of a society that, through its cultural institutions and shared beliefs, resisted erasure and maintained its distinct identity. This explains how India could experience localized military defeats, such as the conquest of Sindh, but avoid the comprehensive cultural transformation seen in other conquered regions.

Individual Bravery and Leadership

The narrative of Indian resistance is replete with instances of extraordinary individual heroism and strategic acumen demonstrated by its leaders.

Raja Dahir and Queen Ranibai embody this spirit. Despite the eventual fall of Sindh, Raja Dahir fought a "heroic fight" at Rawar, leading his army with "great spirit, courage and valour" until his death. His widow, Queen Ranibai, refused to surrender the fort, orchestrating a "heroic defense" and performing Jauhar with other besieged ladies, a powerful act of collective defiance.

Nagabhata I of the Gurjara-Pratihara dynasty demonstrated critical leadership by successfully forming a confederacy and decisively defeating the Arab army under Junaid in 738 CE, marking a pivotal moment that halted Arab expansion into northern India.

Avanijanashraya Pulakeshin, a Chalukya general, earned high praise for his repulsion of the Arab invasion at Navsari in 738-739 CE. His overlord, Vikramaditya II, eulogized him as a "solid pillar of Dakshinpath" and "defeater of those who cannot be defeated," underscoring the significance of his military achievement.

Bappa Rawal of Mewar, a young warrior, rallied smaller states in Rajasthan and Gujarat, successfully pushing back the Arab invasion that had threatened Chittor. He is famously credited with killing the Arab leader Emir Junaid during the Battle of Rajasthan.

Lalitaditya Muktapida, the Karkota king of Kashmir, showcased audacious strategy by modernizing his army and launching pre-emptive strikes against Junayd's forces, inflicting a crushing defeat and forming crucial military alliances to secure his frontiers.

In the 11th century, Raja Suheldev led a remarkable confederation of 17 Hindu kings against the Turkic invader Salar Masud Ghazni, completely annihilating his army at the Battle of Bahraich. This event stands as a powerful testament to the continued capacity for collective resistance among Indian rulers. These individual acts of bravery and strategic leadership, often in concert with broader alliances, collectively forged the "Avengers of Ancient India."

Table 3: Comparative Military Strengths: Indian vs. Arab Forces

The Enduring Legacy: Impact and Historiography

Limited Geographical and Political Impact of Arab Expansion

The sustained and formidable Indian resistance ensured that the Arab expansion into the subcontinent largely ceased by 743 CE, with Arab forces losing their temporary conquests in Rajasthan and Gujarat. This marked a "complete halt of Arab expansionism" on this particular front, a stark contrast to their rapid successes elsewhere. Beyond the initial foothold in Sindh, the Arab conquest had "very little impact on Indian politics" and demonstrably "could not break India's military might". Sindh itself remained geographically isolated from the broader Indian landmass, and its inherent economic limitations hampered the Arabs' capacity to maintain a sufficiently strong army for further, deeper conquests. Ultimately, the weakening control of the central Caliphate led to the overthrow of direct Arab rule in Sindh. By 871 CE, indigenous Muslim dynasties, such as the Soomras and Sammas, had established themselves, further limiting the direct political legacy of the initial Arab conquest. Consequently, the conquest of Sindh is often characterized by historians as "a mere episode in the history of India and Islam, a triumph without result" in terms of its broader political reach and lasting impact on the subcontinent.

Cultural Exchange and Intellectual Contributions Despite Conflict

Despite the military conflicts, the Arab conquest of Sindh paradoxically initiated a period of significant cultural exchange. The Arabs, particularly in Sindh, adopted a policy of tolerance, allowing Hindus to practice their faith, which fostered a degree of mutual respect and interaction. This approach fostered an environment where Arabs gained valuable knowledge from India across various fields. They learned from Indian advancements in astrology, medicine, and philosophy. Crucially, Indian mathematics, including the revolutionary concept of zero, was transmitted to the Islamic world and subsequently reached Europe via Arab scholars. Indian scholars visited Baghdad during the reign of Khalifa Mansur (757-774 CE), bringing with them seminal works like Brahmagupta's Brahmasiddhanta and Khandakhadyaka, which were translated into Arabic. This process continued under Harun al-Rashid, with Aryabhatta's Suryasiddhanta also being translated. Even literary works like the Panchatantra were translated into Arabic, forming the basis for Aesop's fables in the West.

Trade links between India and the Arab world expanded significantly, with Sindh becoming a vital commercial hub. Indian traders continued to explore markets in Iraq and Iran, while Indian physicians and master craftsmen were welcomed in Baghdad. The cultural influence was reciprocal; Arab architects even adopted Indian architectural concepts in their constructions. The Sindhi language itself evolved to incorporate a mixture of Arabic and Sanskrit elements.

The inability of the Arabs to establish widespread and deep political control over the Indian subcontinent meant that a complete cultural imposition, as observed in other conquered lands, did not occur. Instead, the limited political foothold in Sindh, coupled with the strong resistance encountered elsewhere, necessitated a more tolerant administrative approach and fostered a unique environment for mutual learning and exchange. The inability to militarily dominate led to a necessity for accommodation and cultural interaction. This is a crucial, counter-intuitive outcome: the "resilience" of India was not just about preventing conquest but about shaping the nature of interaction with the invaders. The Arabs' failure to fully conquer led to a unique period of cultural synthesis where India, rather than being a passive recipient, actively contributed to the intellectual flourishing of the Islamic world. This demonstrates how resistance can lead to unexpected positive outcomes, transforming a potential subjugation into a period of mutual, albeit unequal, cultural enrichment. It reframes the "failure" of Arab conquest as a success for Indian civilizational continuity and influence, demonstrating a profound adaptive capacity.

The Long-Term Significance of Sustained Resistance

The centuries of Indian resistance, particularly against the early Arab invasions, profoundly shaped the subsequent course of Indian history. This demonstrated unequivocally that India was not an "easy prize" and that its civilization possessed an inherent will to fight and preserve its patrimony. While the Arab conquest of Sindh did, in a limited sense, pave the way for later Turkish invasions , the strong and persistent resistance encountered by the Arabs meant that subsequent Turkic incursions (such as those by the Ghaznavids and Ghurids) faced a fundamentally different, more hardened and resilient landscape. This led to a protracted and bloody affair that, even after centuries, did not fully succeed in converting the vast majority of Hindus.

Scholarly Debates on the Extent and Nature of Indian Resilience

There exists a significant scholarly debate that actively challenges the long-held "meek Hindu" narrative, instead emphasizing the "Heroic Hindu Resistance to Muslim Invaders". Historians like Dr. Ram Gopal Misra have meticulously documented this sustained politico-military and cultural resistance, bringing to light often-ignored aspects of Indian history. Some scholars, including prominent Muslim poets, have even lamented Islam's "failure" to fully conquer and convert India, contrasting it with their comprehensive successes in other regions.

Conversely, some historical interpretations, such as that by Will Durant, describe the Muslim conquest as "probably the bloodiest story in history," attributing Indian defeats to internal divisions and the "unnerving" influence of religions like Buddhism and Jainism. However, counter-arguments highlight that Rajput kingdoms won a significant number of battles against invaders, and that a constant flow of jihadists and mercenaries was required to maintain the invaders' momentum, indicating the intensity of the resistance. The scholarly discussion also delves into the complex role of social divisions, particularly the caste system, as both a potential weakness that could be exploited and, paradoxically, a factor in the long-term resilience of Indian society. This ongoing historiographical re-evaluation underscores the complexity and multi-faceted nature of India's response to these early invasions.

Conclusion: A Testament to Unyielding Spirit

The early Arab invasions of India, while achieving a localized conquest of Sindh, ultimately encountered an unparalleled and sustained resistance across the subcontinent. This resilience was not a singular event but a multi-faceted, multi-generational effort involving powerful dynasties such as the Gurjara-Pratiharas, the Chalukyas, the Rashtrakutas, and various regional kingdoms in Kashmir and Rajasthan. Their strategies encompassed military adaptations, the construction of sophisticated defensive fortifications, and the crucial formation of temporary but effective confederacies that transcended typical inter-state rivalries.

Crucially, this enduring resistance was underpinned by a deep-seated cultural and religious identity. Institutions like temples served as vital centers of societal cohesion, preserving traditions and beliefs even when political structures faced challenges. This inherent resilience of the Indian civilization allowed it to absorb military shocks without succumbing to widespread cultural or religious transformation, a stark contrast to the fate of other regions conquered by the Caliphate.

The "Avengers of Ancient India" were not merely individual heroes or armies; they represented the collective spirit of a civilization that demonstrated an extraordinary capacity to adapt, fight, and endure. Their actions fundamentally limited the geographical and political impact of the early Arab invasions, thereby shaping the subsequent course of Indian history. This period stands as a powerful testament to India's profound capacity for self-preservation and its unyielding spirit in the face of formidable external pressures.