India’s Chenab Diversion Study and the Future of Indus Water Sharing

As India evaluates new water utilization strategies under the Indus Waters Treaty, the Chenab River study could mark a pivotal shift in regional water diplomacy and resource management.

India has initiated a pre-feasibility study to explore diverting water from the Chenab River, a western tributary of the Indus that originates in Himachal Pradesh, flows through Jammu and Kashmir, and enters Pakistan. This is a bold, long-overdue move made entirely within the legal boundaries of the Indus Waters Treaty (IWT), a treaty that, for over six decades, has disproportionately favored Pakistan.

Despite being the upper riparian and home to the river’s origin, India has historically shown restraint, honoring a treaty that gives Pakistan control over 80% of the Indus river system's waters, while India is restricted to just 20%, despite having a population over six times larger and growing demands across agriculture, industry, and urban centers.

Now, with the Chenab diversion study, India is simply exploring how to better utilize the share of water it is already entitled to — not violating the treaty, but finally asserting its legitimate rights.

What’s Driving India’s Water Strategy

The Indus Waters Treaty, signed in 1960 under World Bank mediation, has often been hailed as a model of water-sharing. But in reality, it has deeply constrained India’s water usage for decades, limiting its ability to develop projects on rivers that originate within its own territory.

India's move to study the diversion of the Chenab is a strategic, rational step given three major factors:

- India’s Water Stress: Water scarcity in Punjab, Haryana, Rajasthan, and Delhi is reaching critical levels. Farmers, industries, and urban centers urgently need sustainable water sources. Diverting water that legally belongs to India is not just justified, it is necessary.

- Pakistan’s Water Wastage: Pakistan wastes an estimated $5–10 billion worth of water every year, primarily due to inefficient irrigation, poor infrastructure, and lack of political will to invest in long-term conservation. It has failed to build sufficient reservoirs, letting a significant portion of its water drain into the sea. Blaming India, while continuing with such mismanagement, is neither responsible nor sustainable.

- Changing Climate and Demographics: With rising populations and increasing climate volatility, rigid treaties from the 20th century no longer suit 21st-century needs. India is not withdrawing from the treaty but is reasserting the need to review and balance an outdated arrangement.

Pakistan’s Predictable Reaction And the Flawed Logic Behind It

As expected, Pakistan has voiced strong objections. Officials have claimed that the Chenab’s flow has reduced from 27,000 cusecs to below 5,000 cusecs, affecting rice cultivation. However, fluctuations in river flow are not unusual in pre-monsoon seasons, and India has not constructed any diversion yet only a study is underway.

Rather than address its internal issues, such as outdated irrigation systems, illegal groundwater extraction, and absence of major storage dams Pakistan continues to externalize blame, using water as a political tool. In fact, some voices within Pakistan have irresponsibly suggested retaliatory actions, including military threats against Indian dams, a dangerous and baseless proposition.

Ironically, Pakistan has never agreed to a treaty with upstream nations like Afghanistan for the Kabul River, yet demands strict compliance from India. The hypocrisy is clear.

India’s Utilization Plans

India has continued to supply water beyond its mandated share. In fact, many Indian analysts believe that India has over-complied with the treaty, even during periods of severe drought. Now, as the government contemplates infrastructure worth ₹1 lakh crore (~$12 billion USD) to redirect water to drought-prone Indian states, it is well within its rights.

Some Indian officials have also hinted that if a renegotiation ever occurs, India could seek up to 40–45% of the Indus waters, still leaving Pakistan with the majority. That is not an act of aggression, it’s a logical redistribution based on changing realities.

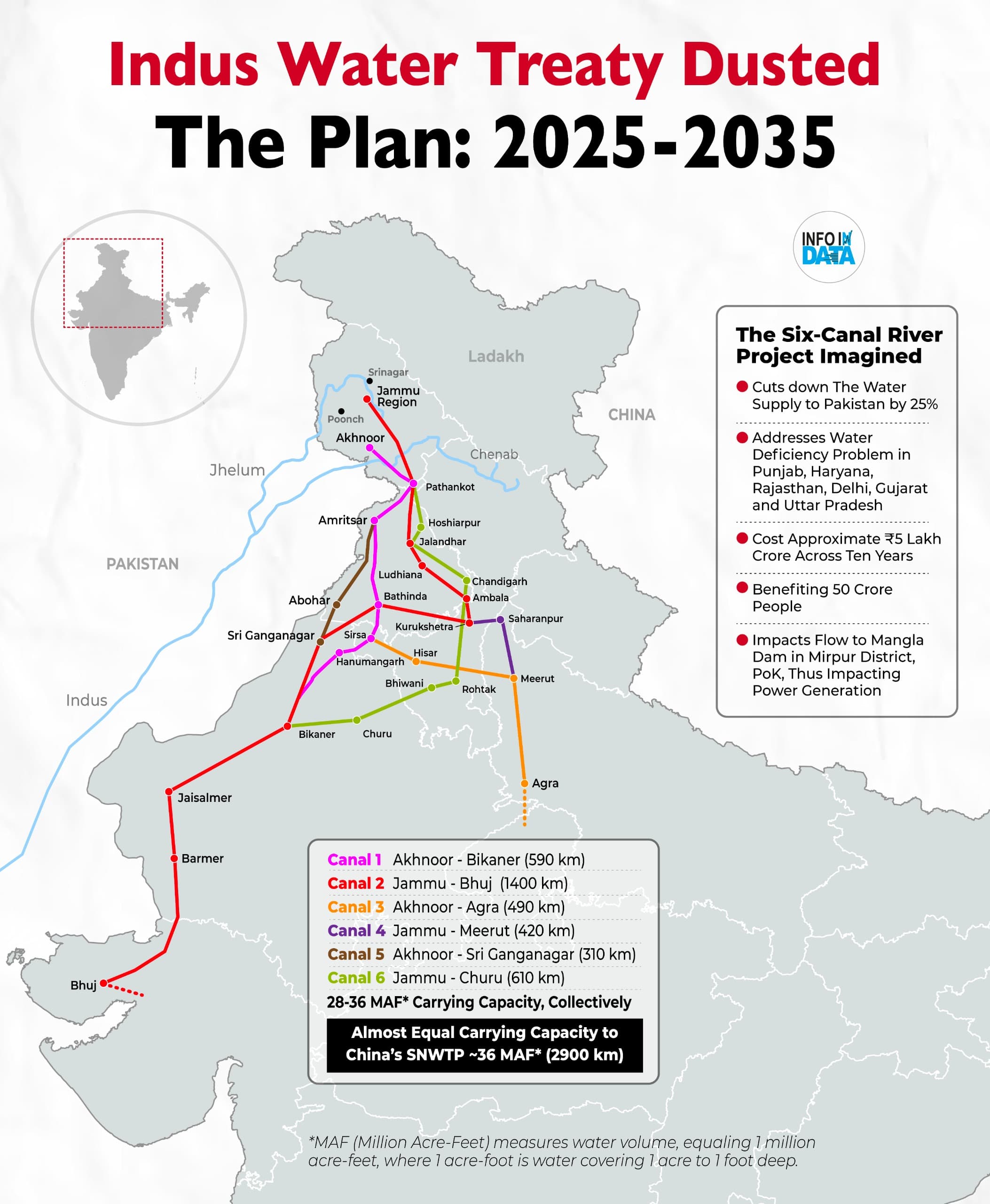

Projects like the Chenab–Beas–Sutlej–Yamuna canal links could channel water through northern and western India, eventually helping up to 500 million citizens. This is not just about national interest, it’s about human survival, climate resilience, and regional stability.

The Path Forward: Rethink, Reform, and Rebalance

India’s actions are rooted in law, logic, and necessity. If Pakistan genuinely wants peace and stability, it should:

- Fix its internal water governance: Modernize canals, reduce agricultural runoff, and stop blaming India for self-inflicted shortages.

- Engage in realistic dialogue: Understand that no treaty is eternal, especially when it ignores demographic and environmental shifts.

- Stop weaponizing water diplomatically: Threats and alarmist rhetoric help no one. What’s needed is cooperation, not confrontation.

India has shown patience and responsibility for over sixty years. But the time has come to assert its rightful share, ensure water for its people, and demand accountability from its neighbors.

Conclusion: Assertive, Not Aggressive

India’s Chenab diversion study is not an act of hostility, it is a reclamation of rights. In a world grappling with climate shocks and resource scarcity, every nation must prioritize its survival. India is doing just that, within the bounds of international law, and with full transparency.